And now we get to play the Yankees for the pennant.

Does it get any better than this?

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

Monday, October 11, 2010

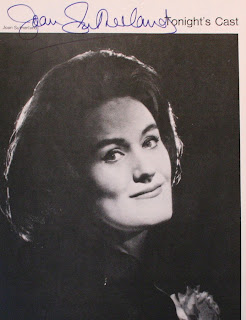

Dame Joan Sutherland, 1926-2010

Any operatic soprano might consider it a dream come true to be known as the greatest singer of her time. But to pay that compliment to Joan Sutherland would be to do her an unforgivable injustice. She was not simply the best Lucia and Norma and Elvira and Amina and Maria Stuarda and Marguerite de Valois and Esclarmonde and Semiramide and Alcina of her day. On the basis of the recorded evidence, she was at least as good as anyone who sang those roles any time in the last hundred years. So it is by no means outrageous to suggest that Joan Sutherland did what she did better than anyone else ever has.

That's what makes those of us who got to hear her in person so grateful. She included all of us, just a bit, in the history she spent her career making. I posted a couple of Sutherland performances last year on her birthday. Here is another one--the final cabaletta from Bellini's La Sonnambula. The heroine Amina has just been cleared of suspicions that she is unfaithful to her fiance. (She walks in her sleep; make up the rest of the story yourself.) Here, assured of her happy ending, she gives voice to that mixture of joy and relief that any soprano experiences upon finding herself still alive at the end of the opera. She sings "Ah! non giunge uman pensiero al contento ond'io son piena." "Ah! human thought cannot comprehend the happiness that fills me." And listening to her, we feel pretty much the same way.

May you all live long enough to hear that trill at 1:55 sung by someone else as spectacularly as Sutherland sings it here. But don't get your hopes up.

That's what makes those of us who got to hear her in person so grateful. She included all of us, just a bit, in the history she spent her career making. I posted a couple of Sutherland performances last year on her birthday. Here is another one--the final cabaletta from Bellini's La Sonnambula. The heroine Amina has just been cleared of suspicions that she is unfaithful to her fiance. (She walks in her sleep; make up the rest of the story yourself.) Here, assured of her happy ending, she gives voice to that mixture of joy and relief that any soprano experiences upon finding herself still alive at the end of the opera. She sings "Ah! non giunge uman pensiero al contento ond'io son piena." "Ah! human thought cannot comprehend the happiness that fills me." And listening to her, we feel pretty much the same way.

May you all live long enough to hear that trill at 1:55 sung by someone else as spectacularly as Sutherland sings it here. But don't get your hopes up.

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Rangers-Rays Series Tied at 2 Games Each

Philosophy must take over at this point. On its face, it's a disappointment to Texas Rangers fans to see their team drop two games in a row and blow a chance to close out the series at home. But here are three considerations that might present themselves to the fan who thinks about it a little more deeply.

SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINE:

Sweeping the Rays might have been a near occasion of the sin of pride. Narrowly winning a hard-fought nerve-racker will make it easier for us to "walk humbly with our God."

ALTRUISM:

Game 5 will give the Rays a second chance at the privilege and pleasure of seeing the great Cliff Lee in action.

RIGHTEOUS VENGEANCE:

A fifth game is necessary if we want to humiliate the Rays by winning the series from them on their home field.

Troublingly, it's the third consideration that appeals to me the most....

SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINE:

Sweeping the Rays might have been a near occasion of the sin of pride. Narrowly winning a hard-fought nerve-racker will make it easier for us to "walk humbly with our God."

ALTRUISM:

Game 5 will give the Rays a second chance at the privilege and pleasure of seeing the great Cliff Lee in action.

RIGHTEOUS VENGEANCE:

A fifth game is necessary if we want to humiliate the Rays by winning the series from them on their home field.

Troublingly, it's the third consideration that appeals to me the most....

Monday, October 4, 2010

Babylonian Poetry, Anyone?

This is fairly geeky, I admit. But I find these recitations of ancient Babylonian poetry fascinating, and especially the passages from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which I read in high school and which I encouraged my middle daughter to read for extra credit last year when she was studying ancient history. (Have I mentioned that we're home schoolers? Is there any need to now?)

This is fairly geeky, I admit. But I find these recitations of ancient Babylonian poetry fascinating, and especially the passages from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which I read in high school and which I encouraged my middle daughter to read for extra credit last year when she was studying ancient history. (Have I mentioned that we're home schoolers? Is there any need to now?)By far the most fascinating character in Gilgamesh is the hero's friend Enkidu, a kind of Rousseauian noble savage whose gradual introduction to civilization--partly at the hands of a prostitute--makes up the poem's most dramatic and compelling plot element. I've never been entirely sure how to pronounce his name, although I've always suspected that the pronunciation I learned in high school--something like "Inky-Doo"--was neither linguistically accurate nor dignified-sounding enough for so admirable a character.

Turns out, based on these recitations, that the correct pronunciation may be en-KEE-doo, which sounds much better to me; and that the title character's name, which I always pronounced with an accent on the first syllable, is actually gil-GAH-mesh.

Live and learn.

Sunday, October 3, 2010

Barack Obama and the BVM

What to make of this? On her recent visit to Spain, First Lady Michelle Obama mentioned that the President carries in his wallet a picture of Mary Help of Christians, one of the titles under which the Blessed Virgin is venerated by Catholics. She is the patroness of the Salesian Order.

What to make of this? On her recent visit to Spain, First Lady Michelle Obama mentioned that the President carries in his wallet a picture of Mary Help of Christians, one of the titles under which the Blessed Virgin is venerated by Catholics. She is the patroness of the Salesian Order.Barack Obama is already under fire from religious right-wingers, some of whom have repeatedly questioned the President's credentials as a Christian and fostered suspicions that he might be a crypto-Muslim. If he turns out to be a crypto-Catholic instead, will Protestant fundamentalists consider that a step up or a step down?

The Feast of St. Francis of Assisi

"Whatever the true religion might be (if there even is one)," I used to say to myself back in my days of spiritual wandering, "then following it--in this world, at least--will have to set you apart as a pretty strange person." And so I looked into some pretty strange religions. But I eventually found the strangest of all, and that's one way I knew it was also the true one.

"Whatever the true religion might be (if there even is one)," I used to say to myself back in my days of spiritual wandering, "then following it--in this world, at least--will have to set you apart as a pretty strange person." And so I looked into some pretty strange religions. But I eventually found the strangest of all, and that's one way I knew it was also the true one.The great genius of Francis of Assisi is that he continually reminds us how strange--how "other-worldly"--authentic Christianity must be. If our faith fits comfortably and conveniently into the life we have decided to make for ourselves, then there's something wrong with it.

One day in winter, as St Francis was going with Brother Leo from

Perugia to St Mary of the Angels, and was suffering greatly from the

cold, he called to Brother Leo, who was walking on before him, and said

to him: "Brother Leo, if it were to please God that the Friars Minor

should give, in all lands, a great example of holiness and edification,

write down, and note carefully, that this would not be perfect joy." A

little further on, St Francis called to him a second time: "O Brother

Leo, if the Friars Minor were to make the lame to walk, if they should

make straight the crooked, chase away demons, give sight to the blind,

hearing to the deaf, speech to the dumb, and, what is even a far

greater work, if they should raise the dead after four days, write that

this would not be perfect joy." Shortly after, he cried out again: "O

Brother Leo, if the Friars Minor knew all languages; if they were

versed in all science; if they could explain all Scripture; if they had

the gift of prophecy, and could reveal, not only all future things, but

likewise the secrets of all consciences and all souls, write that this

would not be perfect joy." After proceeding a few steps farther, he

cried out again with a loud voice: "O Brother Leo, thou little lamb of

God! if the Friars Minor could speak with the tongues of angels; if

they could explain the course of the stars; if they knew the virtues of

all plants; if all the treasures of the earth were revealed to them; if

they were acquainted with the various qualities of all birds, of all

fish, of all animals, of men, of trees, of stones, of roots, and of

waters - write that this would not be perfect joy." Shortly after, he

cried out again: "O Brother Leo, if the Friars Minor had the gift of

preaching so as to convert all infidels to the faith of Christ, write

that this would not be perfect joy." Now when this manner of discourse

had lasted for the space of two miles, Brother Leo wondered much within

himself; and, questioning the saint, he said: "Father, I pray thee

teach me wherein is perfect joy." St Francis answered: "If, when we

shall arrive at St Mary of the Angels, all drenched with rain and

trembling with cold, all covered with mud and exhausted from hunger;

if, when we knock at the convent-gate, the porter should come angrily

and ask us who we are; if, after we have told him, We are two of the

brethren', he should answer angrily, What ye say is not the truth; ye

are but two impostors going about to deceive the world, and take away

the alms of the poor; begone I say'; if then he refuse to open to us,

and leave us outside, exposed to the snow and rain, suffering from cold

and hunger till nightfall - then, if we accept such injustice, such

cruelty and such contempt with patience, without being ruffled and

without murmuring, believing with humility and charity that the porter

really knows us, and that it is God who maketh him to speak thus

against us, write down, O Brother Leo, that this is perfect joy. And if

we knock again, and the porter come out in anger to drive us away with

oaths and blows, as if we were vile impostors, saying, Begone,

miserable robbers! to the hospital, for here you shall neither eat nor

sleep!' - and if we accept all this with patience, with joy, and with

charity, O Brother Leo, write that this indeed is perfect joy. And if,

urged by cold and hunger, we knock again, calling to the porter and

entreating him with many tears to open to us and give us shelter, for

the love of God, and if he come out more angry than before, exclaiming,

These are but importunate rascals, I will deal with them as they

deserve'; and taking a knotted stick, he seize us by the hood, throwing

us on the ground, rolling us in the snow, and shall beat and wound us

with the knots in the stick - if we bear all these injuries with

patience and joy, thinking of the sufferings of our Blessed Lord, which

we would share out of love for him, write, O Brother Leo, that here,

finally, is perfect joy. And now, brother, listen to the conclusion.

Above all the graces and all the gifts of the Holy Spirit which Christ

grants to his friends, is the grace of overcoming oneself, and

accepting willingly, out of love for Christ, all suffering, injury,

discomfort and contempt; for in all other gifts of God we cannot glory,

seeing they proceed not from ourselves but from God, according to the

words of the Apostle, What hast thou that thou hast not received from

God? and if thou hast received it, why dost thou glory as if thou hadst

not received it?' But in the cross of tribulation and affliction we may

glory, because, as the Apostle says again, I will not glory save in the

cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.' Amen."

The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi, Chapter 8

Tony Curtis R.I.P.

I was never particularly a fan of his, but I do like several of his movies--or maybe I should say "movies in which he appears." His big roles--the roles he no doubt was proudest of--are not among my favorites. His portrayal of The Boston Strangler is among those "one-off" performances that movie stars sometimes turn in--a role that uniquely manages to make them look like real actors. Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, Elizabeth Taylor in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Sterling Hayden in Dr. Strangelove. You know what I mean. And I may be the only person I know who doesn't think that Some Like It Hot is a really funny movie. (We all have our blind spots, I guess.)

But I would happily watch Spartacus any time--in spite of Dalton Trumbo's ham-handed and tendentious leftist-allegory screenplay. (Some stories are good enough to survive a bad telling.) And this weekend my 10-year-old sons and I will watch The Vikings--their favorite movie, and one of mine--in tribute to Mr. Curtis. Here's a great scene in which Curtis's character permits Ernest Borgnine's character an honorable Viking death (in a wolf pit). The scene is charged with dramatic irony because neither character knows that they are father and son.

And here is a very different sort of scene, from a movie I would know nothing about were my middle daughter not such a devoted Audrey Hepburn fan--Paris When It Sizzles. Hepburn plays a stenographer hired to help a screenwriter--William Holden--get a script done on time. She imagines each scene as Holden dictates it to her, adding her own suggestions as they go along. Tony Curtis agreed to make this cameo appearance in the movie because Holden--in real life--had had to check into the hospital following a drinking binge and George Axelrod, the producer, needed to keep the rest of the cast and the crew busy. Curtis does an expert job of skewering narcissistic "ac-TORS," himself included.

But I would happily watch Spartacus any time--in spite of Dalton Trumbo's ham-handed and tendentious leftist-allegory screenplay. (Some stories are good enough to survive a bad telling.) And this weekend my 10-year-old sons and I will watch The Vikings--their favorite movie, and one of mine--in tribute to Mr. Curtis. Here's a great scene in which Curtis's character permits Ernest Borgnine's character an honorable Viking death (in a wolf pit). The scene is charged with dramatic irony because neither character knows that they are father and son.

And here is a very different sort of scene, from a movie I would know nothing about were my middle daughter not such a devoted Audrey Hepburn fan--Paris When It Sizzles. Hepburn plays a stenographer hired to help a screenwriter--William Holden--get a script done on time. She imagines each scene as Holden dictates it to her, adding her own suggestions as they go along. Tony Curtis agreed to make this cameo appearance in the movie because Holden--in real life--had had to check into the hospital following a drinking binge and George Axelrod, the producer, needed to keep the rest of the cast and the crew busy. Curtis does an expert job of skewering narcissistic "ac-TORS," himself included.

Saturday, October 2, 2010

Stealing Home

My daughter and I attended our last baseball game of the regular season last night. The Rangers did not win, but it was an exciting game nonetheless -- in part because Josh Hamilton was back in the outfield, diving for fly balls with the same abandon that put him on the DL for most of the month of September; and partly because of this thrilling bit of base running that tied the game for us in the bottom of the ninth.

It was the first time my daughter -- a new baseball fan this season -- had ever seen anyone steal home, and she was impressed. I'll have to show her that it can be even more impressive than that...regardless of what Yogi thought.

It was the first time my daughter -- a new baseball fan this season -- had ever seen anyone steal home, and she was impressed. I'll have to show her that it can be even more impressive than that...regardless of what Yogi thought.

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

The End of Time

All of a sudden, cosmology seems to be the sexy topic in the mainstream media's coverage of science. (Could Stephen Hawking have anything to do with that?)

All of a sudden, cosmology seems to be the sexy topic in the mainstream media's coverage of science. (Could Stephen Hawking have anything to do with that?) Here is what seems to me a rather scatterbrained bit of speculation on the way in which the laws of physics and probability dictate that time will have to come to an end sometime within the next, oh, 3.7 billion years. (Nothing lends scientific credibility to a number like a decimal point, does it?)

I'd be more inclined to dismiss this bit of speculation as quickly as I do most cosmological ruminations if it weren't for a single line in the story that seems to ring true for some reason. The scientists involved "don't know what kind of catastrophe will cause the end of time, but they do say that we won't see it coming."

Hmmm. Do they mean it will be sort of like "a thief in the night"?

Monday, September 27, 2010

"Expert in Humanity"

I'm reading Dayspring, a novel by Harry Sylvester. It's set in New Mexico (which is how it caught my attention--yes, I'm still on my New Mexico kick) and has as its central character an anthropologist who fakes (sort of) a conversion to Catholicism in order to gain access to the Penitentes, members of a secret brotherhood that imposes extreme forms of penance--chiefly flagellation--on its members and that has had a tense relationship with the Catholic hierarchy through most of its history.

After his pretended conversion, the anthropologist finds himself becoming more and more authentically Catholic in his outlook and sensibilities. In one passage, he marvels at all the ways in which the Church's teaching represents a very wise and commonsensical approach to matters of human behavior.

After his pretended conversion, the anthropologist finds himself becoming more and more authentically Catholic in his outlook and sensibilities. In one passage, he marvels at all the ways in which the Church's teaching represents a very wise and commonsensical approach to matters of human behavior.

"On the basic things the Church was always right. By what extraordinary sifting of experience she had become so, he could not understand: it had always amazed him that this basic accuracy and rightness, achieved through some realistic process and over a long time, should be attributed by the Church to anything as ridiculous as what she called revelation. It was not that he and some of the others were ignorant of the Church's being right so often, as that they could not bring themselves to subdue their incredible pride long enough to do what someone else said they should do. Of course, if they believed in God, he thought, it would have been something else again."

What a brilliant miniature portrait of the "scientific" mind contemplating religious truth. And what a devastating analysis of the role played by pride in the origins of sin. The secular world necessarily dismisses any notion that there is such a thing as God's will, but is constantly amazed--and annoyed--that Christianity so often proves to be right about the practical consequences of living in defiance of God's will.

Catholic moral theology is grounded in Catholic anthropology, which means that the Church's calling is twofold: to show God to man, and to show man to himself. When Pope Paul VI, addressing the United Nations General Assembly in October 1965, scandalized representatives of the affluent Western democracies by explicitly condemning artificial birth control, he did so after having referred to the Catholic Church as an "expert in humanity." His claim was greeted with smug condescension. (I still have a vivid memory of CBS's Eric Sevareid being eloquently smug and condescending on the subject.) Forty-five years later it's still possible, perhaps more than ever, to find Catholic claims of "expertise in humanity" being greeted with smug condescension. But it's also possible to find--in every corner of the world--dramatic and tragic evidence that Pope Paul's warnings about "reducing the number of guests at the banquet of life" were right.

Of course, we mustn't attribute that to "anything as ridiculous as what the Church calls revelation."

After his pretended conversion, the anthropologist finds himself becoming more and more authentically Catholic in his outlook and sensibilities. In one passage, he marvels at all the ways in which the Church's teaching represents a very wise and commonsensical approach to matters of human behavior.

After his pretended conversion, the anthropologist finds himself becoming more and more authentically Catholic in his outlook and sensibilities. In one passage, he marvels at all the ways in which the Church's teaching represents a very wise and commonsensical approach to matters of human behavior."On the basic things the Church was always right. By what extraordinary sifting of experience she had become so, he could not understand: it had always amazed him that this basic accuracy and rightness, achieved through some realistic process and over a long time, should be attributed by the Church to anything as ridiculous as what she called revelation. It was not that he and some of the others were ignorant of the Church's being right so often, as that they could not bring themselves to subdue their incredible pride long enough to do what someone else said they should do. Of course, if they believed in God, he thought, it would have been something else again."

What a brilliant miniature portrait of the "scientific" mind contemplating religious truth. And what a devastating analysis of the role played by pride in the origins of sin. The secular world necessarily dismisses any notion that there is such a thing as God's will, but is constantly amazed--and annoyed--that Christianity so often proves to be right about the practical consequences of living in defiance of God's will.

Catholic moral theology is grounded in Catholic anthropology, which means that the Church's calling is twofold: to show God to man, and to show man to himself. When Pope Paul VI, addressing the United Nations General Assembly in October 1965, scandalized representatives of the affluent Western democracies by explicitly condemning artificial birth control, he did so after having referred to the Catholic Church as an "expert in humanity." His claim was greeted with smug condescension. (I still have a vivid memory of CBS's Eric Sevareid being eloquently smug and condescending on the subject.) Forty-five years later it's still possible, perhaps more than ever, to find Catholic claims of "expertise in humanity" being greeted with smug condescension. But it's also possible to find--in every corner of the world--dramatic and tragic evidence that Pope Paul's warnings about "reducing the number of guests at the banquet of life" were right.

Of course, we mustn't attribute that to "anything as ridiculous as what the Church calls revelation."

Stephen Hawking, Theologian?

The physicist Stephen Barr thinks that there is less to Stephen Hawking's latest speculations about God and cosmology than Hawking's publisher and the secular media would like there to be. As I read Prof. Barr's explanation of what Hawking and his co-author Leonard Mlodinow are arguing in The Grand Design, it occurred to me that their claims are not only not antagonistic to the claims of religion, but that they might actually be seen as pointing toward the validity of some of those claims.

But I was a little too lazy and way too scientifically ignorant to undertake an exploration of that subject. Now, fortunately, someone who is up to the task has done it, and his analysis, at Mike Flynn's Journal, is well worth reading.

My only regret in linking to the post is that now I'll never be able to pass off as my own this great Mary Midgley line:

"People who refuse to have anything to do with philosophy have become enslaved to outdated forms of it."

But I was a little too lazy and way too scientifically ignorant to undertake an exploration of that subject. Now, fortunately, someone who is up to the task has done it, and his analysis, at Mike Flynn's Journal, is well worth reading.

My only regret in linking to the post is that now I'll never be able to pass off as my own this great Mary Midgley line:

"People who refuse to have anything to do with philosophy have become enslaved to outdated forms of it."

Two Cheers for Robin Le Poidevin

It long ago ceased to be fun pointing out ways in which Richard Dawkins embarrasses himself when he pretends to be a philosopher. But Robin Le Poidevin, professor of metaphysics at the University of Leeds, still finds the temptation irresistible and, in succumbing to it, makes a point well worth making in a post at the OUPblog.

One of the pillars on which Dawkins's argument against the existence of God rests in his book The God Delusion is his contention that God would have to be almost infinitely complex to be the creator and sustainer of an almost infinitely complex universe. Simply knowing such a universe fully would make an omniscient God at least as complex as the knowledge itself. With this "straw god" firmly in place, Dawkins invokes Occam's Razor to argue that natural evolution is a simpler and therefore a logically preferable explanation for the existence of the world. (You can read this argument in full in Chapter 4 of The God Delusion.)

Dawkins seems unaware, at least within the context of the argument as he presents it, that the concept of a "complex God" flies in the face of orthodox Christian theology. Christians in the Thomistic tradition--which is to say Roman Catholics and a fair number of Protestants--hold to the concept of a "simple God." God acting in different ways at different times and in different places; God "responding to" the actions of human beings; God "working out" his will sequentially through history; God knowing a hundred bazillion separate facts, if you will; these are the perceptions of God as they occur necessarily to finite human beings, but they cannot be essentially true of the "uncaused cause" of the universe in whom Christians, Jews, Muslims, and a fair number of "virtuous pagans" have believed over the centuries. The basics of this philosophical position can be found in Part I, Question 3 of the Summa Theologiae.

Prof. Le Poidevin pinpoints Dawkins's mistake in his blog post:

One of the pillars on which Dawkins's argument against the existence of God rests in his book The God Delusion is his contention that God would have to be almost infinitely complex to be the creator and sustainer of an almost infinitely complex universe. Simply knowing such a universe fully would make an omniscient God at least as complex as the knowledge itself. With this "straw god" firmly in place, Dawkins invokes Occam's Razor to argue that natural evolution is a simpler and therefore a logically preferable explanation for the existence of the world. (You can read this argument in full in Chapter 4 of The God Delusion.)

Dawkins seems unaware, at least within the context of the argument as he presents it, that the concept of a "complex God" flies in the face of orthodox Christian theology. Christians in the Thomistic tradition--which is to say Roman Catholics and a fair number of Protestants--hold to the concept of a "simple God." God acting in different ways at different times and in different places; God "responding to" the actions of human beings; God "working out" his will sequentially through history; God knowing a hundred bazillion separate facts, if you will; these are the perceptions of God as they occur necessarily to finite human beings, but they cannot be essentially true of the "uncaused cause" of the universe in whom Christians, Jews, Muslims, and a fair number of "virtuous pagans" have believed over the centuries. The basics of this philosophical position can be found in Part I, Question 3 of the Summa Theologiae.

Prof. Le Poidevin pinpoints Dawkins's mistake in his blog post:

"When the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz opined that God had created ‘the best of all possible worlds,’ his view was mercilessly lampooned in Voltaire’s satirical novel Candide. ‘Best’ here, however, does not mean most agreeable, but rather where the greatest variety is produced by the simplest laws. And indeed it is a requirement on scientific explanation that it not involve needless complexity. Elegant simplicity is the ideal.

Perhaps God is like that: his understanding and capacities may be infinitely complex, but the underlying nature that gives rise to that complexity may be relatively simple. If so, then it isn’t a given that the probability of such a being is enormously improbable. And if God is not clearly improbable, then atheism is not the default position."

A nice encapsulation of the philosophical principle. Thomists, however, would correct Prof. Le Poidevin in one detail. God is not "relatively" simple; he is (as St. Thomas Aquinas termed it) omnino simplex--absolutely, altogether simple.

Prof. Le Poidevin moves on from this point to a philosophical defense of agnosticism and gets into a bit of trouble, I think--which is why I'm giving him only two cheers. I'll say something about agnosticism in another post.

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Close Encounters of the Worst Kind

So humanity's first contact with intelligent extraterrestrial life is to be coordinated by the United Nations?

So humanity's first contact with intelligent extraterrestrial life is to be coordinated by the United Nations?We're doomed.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

The Rangers Clinch!

No one with a shred of human compassion will begrudge Texas Rangers fans their moment of triumph today. This is beyond question the best Rangers team ever to make it into the absurdly expanded major league baseball post-season ( in which the world championship is now decided in a combined best-of-nineteen-game playoff).

No one with a shred of human compassion will begrudge Texas Rangers fans their moment of triumph today. This is beyond question the best Rangers team ever to make it into the absurdly expanded major league baseball post-season ( in which the world championship is now decided in a combined best-of-nineteen-game playoff).The Woodwards will be attending the first home game of the division series, against either the Yankees or the Rays, and we're pretty keyed up about it. The last post-season game I attended in person was the legendary third game of the 1975 World Series. Surely I'm entitled to a little excitement once every 35 years....

Friday, September 24, 2010

Eddie Fisher R.I.P.

He had better pipes than Frank Sinatra, better than Tony Bennett. The first time I ever noticed that a human voice can be beautiful, I was seven or eight, and I was listening to Eddie Fisher sing something or other on the radio.

One might wish that his musical taste had been as good as that voice. He got very rich singing some very bad songs. But here he is singing a great one.

One interesting sociological note. In 1959, Eddie Fisher was arguably the biggest recording star in the United States, and his hit TV show was making him a bigger star than ever. But in March of that year, amid the scandal of his having divorced his wife Debbie Reynolds in order to marry Elizabeth Taylor, NBC cancelled the show.

O tempora, O mores....

One might wish that his musical taste had been as good as that voice. He got very rich singing some very bad songs. But here he is singing a great one.

One interesting sociological note. In 1959, Eddie Fisher was arguably the biggest recording star in the United States, and his hit TV show was making him a bigger star than ever. But in March of that year, amid the scandal of his having divorced his wife Debbie Reynolds in order to marry Elizabeth Taylor, NBC cancelled the show.

O tempora, O mores....

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

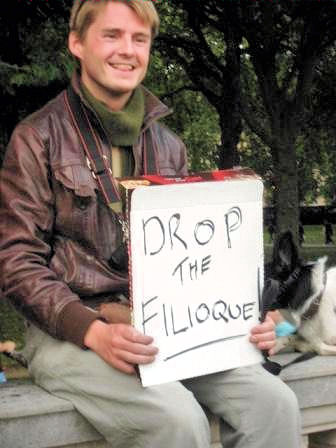

Yeah, But What About Monothelitism?

Of all the protesters holding up signs as the Pope traveled through Great Britain last week, something tells me that this guy is the one His Holiness would most have enjoyed stopping to talk with.

The Faith of the Founders

I can't think of any topic of civic discourse in the last 50 years that has been more pointless or that has provided the opportunity for the parading of more ignorance and ill will than the question of whether the United States is a "Christian nation." Particularly discouraging has been some right-wing demagogues' portrayal of the Founding Fathers as more or less a collection of Billy Grahams in powdered wigs.

Now, finally, someone with some knowledge of the subject and a dispassionate interest in judging the matter accurately has turned his attention to what Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin, Hamilton and all those other guys on various denominations of U. S. currency actually believed. The results are not particularly surprising to anyone who has studied American history, but they should still be an eye-opener to most Americans -- both left and right.

Now, finally, someone with some knowledge of the subject and a dispassionate interest in judging the matter accurately has turned his attention to what Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin, Hamilton and all those other guys on various denominations of U. S. currency actually believed. The results are not particularly surprising to anyone who has studied American history, but they should still be an eye-opener to most Americans -- both left and right.

Bottom line: The Founding Fathers mostly believed in God (if only the God of the Enlightenment), which puts them at odds with most of the secular Left. But relatively few of the Founding Fathers believed that Jesus was the divinely begotten Son of that God, which puts them equally at odds with the Christian Right.

Read the fascinating details here.

(By the way, one curious omission from the First Things review (although I hope not from Prof. Holmes's book itself) is Charles Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first great Catholic figure in the history of the new Republic. A wealthy Maryland farmer--and slave owner--he nonetheless advocated a gradual end to slavery, introducing abolitionist legislation in the Maryland senate and promoting the establishment of Liberia as a nation home for emancipated and "repatriated" slaves. That makes his beliefs with regard to "America's original sin" considerably more admirable than those of most of his fellow Founding Fathers, especially the slave-holding ones.)

(By the way, one curious omission from the First Things review (although I hope not from Prof. Holmes's book itself) is Charles Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first great Catholic figure in the history of the new Republic. A wealthy Maryland farmer--and slave owner--he nonetheless advocated a gradual end to slavery, introducing abolitionist legislation in the Maryland senate and promoting the establishment of Liberia as a nation home for emancipated and "repatriated" slaves. That makes his beliefs with regard to "America's original sin" considerably more admirable than those of most of his fellow Founding Fathers, especially the slave-holding ones.)

Now, finally, someone with some knowledge of the subject and a dispassionate interest in judging the matter accurately has turned his attention to what Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin, Hamilton and all those other guys on various denominations of U. S. currency actually believed. The results are not particularly surprising to anyone who has studied American history, but they should still be an eye-opener to most Americans -- both left and right.

Now, finally, someone with some knowledge of the subject and a dispassionate interest in judging the matter accurately has turned his attention to what Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin, Hamilton and all those other guys on various denominations of U. S. currency actually believed. The results are not particularly surprising to anyone who has studied American history, but they should still be an eye-opener to most Americans -- both left and right.Bottom line: The Founding Fathers mostly believed in God (if only the God of the Enlightenment), which puts them at odds with most of the secular Left. But relatively few of the Founding Fathers believed that Jesus was the divinely begotten Son of that God, which puts them equally at odds with the Christian Right.

Read the fascinating details here.

(By the way, one curious omission from the First Things review (although I hope not from Prof. Holmes's book itself) is Charles Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first great Catholic figure in the history of the new Republic. A wealthy Maryland farmer--and slave owner--he nonetheless advocated a gradual end to slavery, introducing abolitionist legislation in the Maryland senate and promoting the establishment of Liberia as a nation home for emancipated and "repatriated" slaves. That makes his beliefs with regard to "America's original sin" considerably more admirable than those of most of his fellow Founding Fathers, especially the slave-holding ones.)

(By the way, one curious omission from the First Things review (although I hope not from Prof. Holmes's book itself) is Charles Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first great Catholic figure in the history of the new Republic. A wealthy Maryland farmer--and slave owner--he nonetheless advocated a gradual end to slavery, introducing abolitionist legislation in the Maryland senate and promoting the establishment of Liberia as a nation home for emancipated and "repatriated" slaves. That makes his beliefs with regard to "America's original sin" considerably more admirable than those of most of his fellow Founding Fathers, especially the slave-holding ones.)

Sunday, September 19, 2010

One More Thought About Newman

How many saints or beati of the Catholic Church rank with John Henry Newman -- not as examples of heroic virtue but as major literary figures? Here are the ones who come to mind:

St. Augustine

St. John of the Cross

St. Teresa of Avila

Anybody else?

UPDATE: Kind of embarrassing to forget St. Thomas More....

St. Augustine

St. John of the Cross

St. Teresa of Avila

Anybody else?

UPDATE: Kind of embarrassing to forget St. Thomas More....

Blessed John Henry Newman

A great day for the Church and for that multitude of us who revere Cardinal Newman as a thinker, a writer, and a model of holiness.

Nothing that happens in the Church nowadays can be absolutely free of partisan tensions. Newman, certainly, is too central and towering a figure in Catholic history to escape being laid claim to by a wide and contentious assortment of advocates for this or that "brand" of Catholicism. And so it is that we get Garry Wills (writing in that distinguished theological journal the New York Review of Books) calling Newman a "radical"--like Wills himself, get it?--and Pope Benedict "the best-dressed liar in the world." I'm old enough to have had at one time a tempered admiration for Garry Wills, back in his Bare Ruined Choirs days. Lately I find myself hoping that Wills will wake up in his right mind one of these days and instantly regret pretty much everything he's published over the last 25 years -- well, maybe with the exception of Lincoln at Gettysburg and his translation of Martial's Epigrams, two intelligent if wildly different studies in the power of language.

In one sense, Newman certainly was a "radical"; his conversion from Anglicanism to Catholicism is a perfect object lesson in Christian radicalism--a return to the roots of truth. But he was no "radical Catholic" in the way Garry Wills would like to think. Yes, Newman championed conscience in his famous toast--but conscience as the Catechism understands it, not as Hans Kung or Joan Chittister or Nancy Pelosi misrepresents it. And yes, Newman expressed reservations about the First Vatican Council's definition of the dogma of papal infallibility--but as a prudential matter, a question of timing and policy, not because he himself did not believe the dogma. (He did believe it, and wrote iron-clad defenses of it.) These are all matters of record for anyone willing to pay attention to the record--Newman's own writings, the standard biographies (Ker, Zeno, Martin), histories of the First Vatican Council. Yet the legend of "Newman the dissenter" is still resurrected from time to time by hero-starved Catholic dissenters, in much the same way that Protestants still talk about the Council of Nicaea as a Catholic hijacking of the New Testament Church, or anti-Catholic secularists still talk about Pius XII's collaboration with the Nazis. Some lies are simply too useful to abandon.

What Newman genuinely offers us today, above all, is not an endorsement of one side or another in the Catholic culture wars, but rather a call to action...oops, let me rephrase that...a warning and an encouragement about the real culture war in which Western civilization is now embroiled. It is the war against moral and epistemological relativism, and Newman gave his whole adult life in a struggle against it. Here is one of his most famous statements on the subject--the "Biglietto Address," the short speech he made in 1879 when he accepted the cardinal's biretta. (Newman's use of the term liberalism here is perhaps unfortunate--even though it was precisely the correct term at the time--because it suggests to modern ears that relativism is tied in some way to a political philosophy. It need not be.)

In any case, Newman's words are startlingly prophetic. And, in their tone of calm Christian hope at the end, they are comforting:

For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion. Never did Holy Church need champions against it more sorely than now, when, alas! it is an error overspreading, as a snare, the whole earth; and on this great occasion, when it is natural for one who is in my place to look out upon the world, and upon Holy Church as it is, and upon her future, it will not, I hope, be considered out of place, if I renew the protest against it which I have made so often.

Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another, and this is the teaching which is gaining substance and force daily. It is inconsistent with any recognition of any religion, as true. It teaches that all are to be tolerated, for all are matters of opinion. Revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, not miraculous; and it is the right of each individual to make it say just what strikes his fancy. Devotion is not necessarily founded on faith. Men may go to Protestant Churches and to Catholic, may get good from both and belong to neither. They may fraternise together in spiritual thoughts and feelings, without having any views at all of doctrine in common, or seeing the need of them. Since, then, religion is so personal a peculiarity and so private a possession, we must of necessity ignore it in the intercourse of man with man. If a man puts on a new religion every morning, what is that to you? It is as impertinent to think about a man's religion as about his sources of income or his management of his family. Religion is in no sense the bond of society.

Hitherto the civil Power has been Christian. Even in countries separated from the Church, as in my own, the dictum was in force, when I was young, that: "Christianity was the law of the land". Now, everywhere that goodly framework of society, which is the creation of Christianity, is throwing off Christianity. The dictum to which I have referred, with a hundred others which followed upon it, is gone, or is going everywhere; and, by the end of the century, unless the Almighty interferes, it will be forgotten. Hitherto, it has been considered that religion alone, with its supernatural sanctions, was strong enough to secure submission of the masses of our population to law and order; now the Philosophers and Politicians are bent on satisfying this problem without the aid of Christianity. Instead of the Church's authority and teaching, they would substitute first of all a universal and a thoroughly secular education, calculated to bring home to every individual that to be orderly, industrious, and sober, is his personal interest. Then, for great working principles to take the place of religion, for the use of the masses thus carefully educated, it provides — the broad fundamental ethical truths, of justice, benevolence, veracity, and the like; proved experience; and those natural laws which exist and act spontaneously in society, and in social matters, whether physical or psychological; for instance, in government, trade, finance, sanitary experiments, and the intercourse of nations. As to Religion, it is a private luxury, which a man may have if he will; but which of course he must pay for, and which he must not obtrude upon others, or indulge in to their annoyance.

The general character of this great apostasia is one and the same everywhere; but in detail, and in character, it varies in different countries. For myself, I would rather speak of it in my own country, which I know. There, I think it threatens to have a formidable success; though it is not easy to see what will be its ultimate issue. At first sight it might be thought that Englishmen are too religious for a movement which, on the Continent, seems to be founded on infidelity; but the misfortune with us is, that, though it ends in infidelity as in other places, it does not necessarily arise out of infidelity. It must be recollected that the religious sects, which sprang up in England three centuries ago, and which are so powerful now, have ever been fiercely opposed to the Union of Church and State, and would advocate the un-Christianising of the monarchy and all that belongs to it, under the notion that such a catastrophe would make Christianity much more pure and much more powerful. Next the liberal principle is forced on us from the necessity of the case. Consider what follows from the very fact of these many sects. They constitute the religion, it is supposed, of half the population; and, recollect, our mode of government is popular. Every dozen men taken at random whom you meet in the streets has a share in political power — when you inquire into their forms of belief, perhaps they represent one or other of as many as seven religions; how can they possibly act together in municipal or in national matters, if each insists on the recognition of his own religious denomination? All action would be at a deadlock unless the subject of religion was ignored. We cannot help ourselves. And, thirdly, it must be borne in mind, that there is much in the liberalistic theory which is good and true; for example, not to say more, the precepts of justice, truthfulness, sobriety, self-command, benevolence, which, as I have already noted, are among its avowed principles, and the natural laws of society. It is not till we find that this array of principles is intended to supersede, to block out, religion, that we pronounce it to be evil. There never was a device of the Enemy so cleverly framed and with such promise of success.

And already it has answered to the expectations which have been formed of it. It is sweeping into its own ranks great numbers of able, earnest, virtuous men, elderly men of approved antecedents, young men with a career before them.

Such is the state of things in England, and it is well that it should be realised by all of us; but it must not be supposed for a moment that I am afraid of it.

I lament it deeply, because I foresee that it may be the ruin of many souls; but I have no fear at all that it really can do aught of serious harm to the Word of God, to Holy Church, to our Almighty King, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, Faithful and True, or to His Vicar on earth. Christianity has been too often in what seemed deadly peril, that we should fear for it any new trial now. So far is certain; on the other hand, what is uncertain, and in these great contests commonly is uncertain, and what is commonly a great surprise, when it is witnessed, is the particular mode by which, in the event, Providence rescues and saves His elect inheritance. Sometimes our enemy is turned into a friend; sometimes he is despoiled of that special virulence of evil which was so threatening; sometimes he falls to pieces of himself; sometimes he does just so much as is beneficial, and then is removed. Commonly the Church has nothing more to do than to go on in her own proper duties, in confidence and peace; to stand still and to see the salvation of God.

Mansueti hereditabunt terram,

Et delectabuntur in multitudine pacis.

["The meek will inherit the land,

And they will delight in the abundance of peace."]

Blessed John Henry Newman, pray for us.

Nothing that happens in the Church nowadays can be absolutely free of partisan tensions. Newman, certainly, is too central and towering a figure in Catholic history to escape being laid claim to by a wide and contentious assortment of advocates for this or that "brand" of Catholicism. And so it is that we get Garry Wills (writing in that distinguished theological journal the New York Review of Books) calling Newman a "radical"--like Wills himself, get it?--and Pope Benedict "the best-dressed liar in the world." I'm old enough to have had at one time a tempered admiration for Garry Wills, back in his Bare Ruined Choirs days. Lately I find myself hoping that Wills will wake up in his right mind one of these days and instantly regret pretty much everything he's published over the last 25 years -- well, maybe with the exception of Lincoln at Gettysburg and his translation of Martial's Epigrams, two intelligent if wildly different studies in the power of language.

In one sense, Newman certainly was a "radical"; his conversion from Anglicanism to Catholicism is a perfect object lesson in Christian radicalism--a return to the roots of truth. But he was no "radical Catholic" in the way Garry Wills would like to think. Yes, Newman championed conscience in his famous toast--but conscience as the Catechism understands it, not as Hans Kung or Joan Chittister or Nancy Pelosi misrepresents it. And yes, Newman expressed reservations about the First Vatican Council's definition of the dogma of papal infallibility--but as a prudential matter, a question of timing and policy, not because he himself did not believe the dogma. (He did believe it, and wrote iron-clad defenses of it.) These are all matters of record for anyone willing to pay attention to the record--Newman's own writings, the standard biographies (Ker, Zeno, Martin), histories of the First Vatican Council. Yet the legend of "Newman the dissenter" is still resurrected from time to time by hero-starved Catholic dissenters, in much the same way that Protestants still talk about the Council of Nicaea as a Catholic hijacking of the New Testament Church, or anti-Catholic secularists still talk about Pius XII's collaboration with the Nazis. Some lies are simply too useful to abandon.

What Newman genuinely offers us today, above all, is not an endorsement of one side or another in the Catholic culture wars, but rather a call to action...oops, let me rephrase that...a warning and an encouragement about the real culture war in which Western civilization is now embroiled. It is the war against moral and epistemological relativism, and Newman gave his whole adult life in a struggle against it. Here is one of his most famous statements on the subject--the "Biglietto Address," the short speech he made in 1879 when he accepted the cardinal's biretta. (Newman's use of the term liberalism here is perhaps unfortunate--even though it was precisely the correct term at the time--because it suggests to modern ears that relativism is tied in some way to a political philosophy. It need not be.)

In any case, Newman's words are startlingly prophetic. And, in their tone of calm Christian hope at the end, they are comforting:

For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion. Never did Holy Church need champions against it more sorely than now, when, alas! it is an error overspreading, as a snare, the whole earth; and on this great occasion, when it is natural for one who is in my place to look out upon the world, and upon Holy Church as it is, and upon her future, it will not, I hope, be considered out of place, if I renew the protest against it which I have made so often.

Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another, and this is the teaching which is gaining substance and force daily. It is inconsistent with any recognition of any religion, as true. It teaches that all are to be tolerated, for all are matters of opinion. Revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, not miraculous; and it is the right of each individual to make it say just what strikes his fancy. Devotion is not necessarily founded on faith. Men may go to Protestant Churches and to Catholic, may get good from both and belong to neither. They may fraternise together in spiritual thoughts and feelings, without having any views at all of doctrine in common, or seeing the need of them. Since, then, religion is so personal a peculiarity and so private a possession, we must of necessity ignore it in the intercourse of man with man. If a man puts on a new religion every morning, what is that to you? It is as impertinent to think about a man's religion as about his sources of income or his management of his family. Religion is in no sense the bond of society.

Hitherto the civil Power has been Christian. Even in countries separated from the Church, as in my own, the dictum was in force, when I was young, that: "Christianity was the law of the land". Now, everywhere that goodly framework of society, which is the creation of Christianity, is throwing off Christianity. The dictum to which I have referred, with a hundred others which followed upon it, is gone, or is going everywhere; and, by the end of the century, unless the Almighty interferes, it will be forgotten. Hitherto, it has been considered that religion alone, with its supernatural sanctions, was strong enough to secure submission of the masses of our population to law and order; now the Philosophers and Politicians are bent on satisfying this problem without the aid of Christianity. Instead of the Church's authority and teaching, they would substitute first of all a universal and a thoroughly secular education, calculated to bring home to every individual that to be orderly, industrious, and sober, is his personal interest. Then, for great working principles to take the place of religion, for the use of the masses thus carefully educated, it provides — the broad fundamental ethical truths, of justice, benevolence, veracity, and the like; proved experience; and those natural laws which exist and act spontaneously in society, and in social matters, whether physical or psychological; for instance, in government, trade, finance, sanitary experiments, and the intercourse of nations. As to Religion, it is a private luxury, which a man may have if he will; but which of course he must pay for, and which he must not obtrude upon others, or indulge in to their annoyance.

The general character of this great apostasia is one and the same everywhere; but in detail, and in character, it varies in different countries. For myself, I would rather speak of it in my own country, which I know. There, I think it threatens to have a formidable success; though it is not easy to see what will be its ultimate issue. At first sight it might be thought that Englishmen are too religious for a movement which, on the Continent, seems to be founded on infidelity; but the misfortune with us is, that, though it ends in infidelity as in other places, it does not necessarily arise out of infidelity. It must be recollected that the religious sects, which sprang up in England three centuries ago, and which are so powerful now, have ever been fiercely opposed to the Union of Church and State, and would advocate the un-Christianising of the monarchy and all that belongs to it, under the notion that such a catastrophe would make Christianity much more pure and much more powerful. Next the liberal principle is forced on us from the necessity of the case. Consider what follows from the very fact of these many sects. They constitute the religion, it is supposed, of half the population; and, recollect, our mode of government is popular. Every dozen men taken at random whom you meet in the streets has a share in political power — when you inquire into their forms of belief, perhaps they represent one or other of as many as seven religions; how can they possibly act together in municipal or in national matters, if each insists on the recognition of his own religious denomination? All action would be at a deadlock unless the subject of religion was ignored. We cannot help ourselves. And, thirdly, it must be borne in mind, that there is much in the liberalistic theory which is good and true; for example, not to say more, the precepts of justice, truthfulness, sobriety, self-command, benevolence, which, as I have already noted, are among its avowed principles, and the natural laws of society. It is not till we find that this array of principles is intended to supersede, to block out, religion, that we pronounce it to be evil. There never was a device of the Enemy so cleverly framed and with such promise of success.

And already it has answered to the expectations which have been formed of it. It is sweeping into its own ranks great numbers of able, earnest, virtuous men, elderly men of approved antecedents, young men with a career before them.

Such is the state of things in England, and it is well that it should be realised by all of us; but it must not be supposed for a moment that I am afraid of it.

I lament it deeply, because I foresee that it may be the ruin of many souls; but I have no fear at all that it really can do aught of serious harm to the Word of God, to Holy Church, to our Almighty King, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, Faithful and True, or to His Vicar on earth. Christianity has been too often in what seemed deadly peril, that we should fear for it any new trial now. So far is certain; on the other hand, what is uncertain, and in these great contests commonly is uncertain, and what is commonly a great surprise, when it is witnessed, is the particular mode by which, in the event, Providence rescues and saves His elect inheritance. Sometimes our enemy is turned into a friend; sometimes he is despoiled of that special virulence of evil which was so threatening; sometimes he falls to pieces of himself; sometimes he does just so much as is beneficial, and then is removed. Commonly the Church has nothing more to do than to go on in her own proper duties, in confidence and peace; to stand still and to see the salvation of God.

Mansueti hereditabunt terram,

Et delectabuntur in multitudine pacis.

["The meek will inherit the land,

And they will delight in the abundance of peace."]

Blessed John Henry Newman, pray for us.

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

I've been away from blogging for several days, back in my home town of Louisville, Kentucky, tending to a family emergency. (Prayers for my father's recovery from a serious illness would be deeply appreciated.)

I do find myself with a little time today, though, to pause and wish the Mother of God a happy birthday.

OUR LADIE'S NATIVITYE

Joye in the risinge of our orient starr,

That shall bringe forth the Sunne that lent her light;

Joye in the peace that shall conclude our warre,

And soon rebate the edge of Satan's spight;

Load-starre of all engolfd in worldly waves,

The card and compasse that from shipwracke saves.

The patriark and prophettes were the floures

Which Tyme by course of ages did distill,

And culld into this little cloude the shoures

Whose gracious droppes the world with joy shall fill;

Whose moysture suppleth every soule with grace,

And bringeth life to Adam's dyinge race.

For God, on Earth, she is the royall throne,

The chosen cloth to make His mortall weede;

The quarry to cutt out our Corner-stone,

Soyle full of fruite, yet free from mortall seede;

For heavenly floure she is the Jesse rodd,

The childe of man, the parent of a God.

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Youth and Age and Tommy John Surgery

I guess like most baseball fans, I find this story exceptionally heartbreaking. No major league baseball player's debut in recent years was hyped more than Stephen Strasburg's; and no rookie ever lived up to his hype more convincingly than Strasburg did. Now Strasburg finds himself, at age 22, a man on whom time has already taken its toll. The ironies need no annotation.

Strasburg is handling his misfortune gracefully and with an introspective courage that is rare among people born in 1988. Rare, frankly, among people of any age who must face disappointment on the scale he is facing it. Earlier this season, he realized an ambition that must have occupied him, more or less exclusively, for at least 75 percent of his life. And now the fulfillment of that ambition is in serious jeopardy.

I can't help thinking about the experience of seeing something you've worked 15 years for suddenly taken away from you -- at least temporarily, and perhaps forever. How much harder must the experience be when those 15 years represent pretty much your whole conscious existence. For a person my age, the frustration of "long-term" dreams is something that has probably happened at least a few times in one's life. Eventually we learn that things we once thought represented our one and only chance of happiness--getting this girl or that job--usually aren't as defining a goal as we thought. When we don't get the thing we were certain we had to have, we usually find some other way of being happy and fulfilled. And even more importantly, we find that there are other ways of being happy and fulfilled, knowledge that will be a source of repeated consolation to us as the years and the disappointments roll by.

I can't help thinking about the experience of seeing something you've worked 15 years for suddenly taken away from you -- at least temporarily, and perhaps forever. How much harder must the experience be when those 15 years represent pretty much your whole conscious existence. For a person my age, the frustration of "long-term" dreams is something that has probably happened at least a few times in one's life. Eventually we learn that things we once thought represented our one and only chance of happiness--getting this girl or that job--usually aren't as defining a goal as we thought. When we don't get the thing we were certain we had to have, we usually find some other way of being happy and fulfilled. And even more importantly, we find that there are other ways of being happy and fulfilled, knowledge that will be a source of repeated consolation to us as the years and the disappointments roll by.

Mentally and emotionally, Stephen Strasburg seems to be fine. Every baseball lover has to hope that sometime next year he will be fine physically as well. (And, frankly, I know a few hundred thousand people in north Texas who also hope that he ends up in a Rangers uniform someday.) But how hard a lesson it must be, at age 22, to learn that no merely human aspiration, regardless of how well supported it may be with talent and hard work and desire, can guarantee happiness. People my age often say--to the well-deserved scorn of their juniors--that youth is wasted on the young. But when I reflect back on the way in which disappointment and anxiety loomed unrealistically large for me when I was a young man--because of what I did not yet know--I sometimes think that the wisdom and perspective of age is wasted on the old.

Strasburg is handling his misfortune gracefully and with an introspective courage that is rare among people born in 1988. Rare, frankly, among people of any age who must face disappointment on the scale he is facing it. Earlier this season, he realized an ambition that must have occupied him, more or less exclusively, for at least 75 percent of his life. And now the fulfillment of that ambition is in serious jeopardy.

I can't help thinking about the experience of seeing something you've worked 15 years for suddenly taken away from you -- at least temporarily, and perhaps forever. How much harder must the experience be when those 15 years represent pretty much your whole conscious existence. For a person my age, the frustration of "long-term" dreams is something that has probably happened at least a few times in one's life. Eventually we learn that things we once thought represented our one and only chance of happiness--getting this girl or that job--usually aren't as defining a goal as we thought. When we don't get the thing we were certain we had to have, we usually find some other way of being happy and fulfilled. And even more importantly, we find that there are other ways of being happy and fulfilled, knowledge that will be a source of repeated consolation to us as the years and the disappointments roll by.

I can't help thinking about the experience of seeing something you've worked 15 years for suddenly taken away from you -- at least temporarily, and perhaps forever. How much harder must the experience be when those 15 years represent pretty much your whole conscious existence. For a person my age, the frustration of "long-term" dreams is something that has probably happened at least a few times in one's life. Eventually we learn that things we once thought represented our one and only chance of happiness--getting this girl or that job--usually aren't as defining a goal as we thought. When we don't get the thing we were certain we had to have, we usually find some other way of being happy and fulfilled. And even more importantly, we find that there are other ways of being happy and fulfilled, knowledge that will be a source of repeated consolation to us as the years and the disappointments roll by.Mentally and emotionally, Stephen Strasburg seems to be fine. Every baseball lover has to hope that sometime next year he will be fine physically as well. (And, frankly, I know a few hundred thousand people in north Texas who also hope that he ends up in a Rangers uniform someday.) But how hard a lesson it must be, at age 22, to learn that no merely human aspiration, regardless of how well supported it may be with talent and hard work and desire, can guarantee happiness. People my age often say--to the well-deserved scorn of their juniors--that youth is wasted on the young. But when I reflect back on the way in which disappointment and anxiety loomed unrealistically large for me when I was a young man--because of what I did not yet know--I sometimes think that the wisdom and perspective of age is wasted on the old.

A Cooking Tip (Don't Expect Many of These)

There are ideas so self-evidently right that merely naming them proves their rightness. For example:

BACON PANCAKES.

I know -- it's the sort of revelation that makes you slap your forehead and mutter,"Why didn't I think of that?"

We had some for lunch today after church, preparing them pretty much as in the picture (although, being Texans, we chose Jimmy Dean thick-cut instead of Rath). We kept a small amount of the fat from frying the bacon strips to grease the griddle for the pancakes (which never hurts). And we ate them with pancake syrup.

They were indescribably good. In the words of the old hymn, "All glory, lard, and honor...."

H/T -- Four Pounds Flour

BACON PANCAKES.

I know -- it's the sort of revelation that makes you slap your forehead and mutter,"Why didn't I think of that?"

We had some for lunch today after church, preparing them pretty much as in the picture (although, being Texans, we chose Jimmy Dean thick-cut instead of Rath). We kept a small amount of the fat from frying the bacon strips to grease the griddle for the pancakes (which never hurts). And we ate them with pancake syrup.

They were indescribably good. In the words of the old hymn, "All glory, lard, and honor...."

H/T -- Four Pounds Flour

Thursday, August 26, 2010

D. H. Lawrence and New Mexico

That D. H. Lawrence line in my last post is from a 1928 essay of his, written after his two half-year stays near Taos (on a ranch he purchased in exchange for the manuscript of Sons and Lovers -- make of that what you will, real estate agents!). Maybe the most interesting passage from the essay, entitled "New Mexico," is this:

That D. H. Lawrence line in my last post is from a 1928 essay of his, written after his two half-year stays near Taos (on a ranch he purchased in exchange for the manuscript of Sons and Lovers -- make of that what you will, real estate agents!). Maybe the most interesting passage from the essay, entitled "New Mexico," is this:"Those that have spent morning after morning alone there pitched among the pines above the great proud world of desert will know, almost unbearably, how beautiful it is, how clear and unquestioned is the might of the day. Just day itself is tremendous there. It is so easy to understand that the Aztecs gave hearts of men to the sun. For the sun is not merely hot or scorching, not at all. It is of a brilliant and unchallengeable purity and haughty serenity which would make one sacrifice the heart to it. Ah, yes, in New Mexico the heart is sacrificed to the sun and the human being is left stark, heartless, but undauntedly religious.

And that was the second revelation out there. I had looked over all the world for something that would strike me as religious. The simple piety of some English people, the semi-pagan mystery of some Catholics in southern Italy, the intensity of some Bavarian peasants, the semi-ecstasy of Buddhists or Brahmins: all this had seemed religious all right, as far as the parties concerned were involved, but it didn't involve me. I looked on at the religiousness from the outside. For it is still harder to feel religion at will than to love at will."

Well, that is quite a goulash of romanticism, mysticism, cosmopolitanism, and paganism--which is not a bad four-word description of D. H. Lawrence's literary style. He was obviously a very confused man--more confused than ever on account of the broad experience of life that his 40-odd years of living had brought him. And yet there is something true in those paragraphs.

The quality in nature that leads one to religious insight is not the beauty of nature, or the orderliness of nature, or the goodness of nature. It is the wildness of nature, the bigness of nature, the feeling that nature produces in us of something immensely larger and more powerful than ourselves. Perhaps no one is better situated to be open to such insights than an Englishman, for whom his own local nature is essentially something domesticated and cozy. It is the transcendent feeling that English Romantic poets referred to as a sense of the "sublime." And, tellingly, they pretty much had to travel outside England and its human-scaled natural terrain in order to feel it. The Alps would do it for them. And, if they could have gotten as far as New Mexico, the Rocky Mountains would have done it for them as well.

I believe that I understand, more or less, what D. H. Lawrence felt and wrote about in his description of New Mexico. The immensity of nature that one confronts in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains is, of course, not the only source of religious experience that a person can have. (And I certainly am not willing to let D. H. Lawrence define that religious experience for me. I am in touch with a defining religious authority that Lawrence would not, did not, acknowledge--the Roman Catholic Church. It's the authority that enables me to distinguish between what is metaphysically true--and what is not--in the religious impulse of the Aztec, and the Brahmin, and the Buddhist, and D. H. Lawrence.) But nature, as Lawrence clearly perceived, is a source of one particular religious truth that is hard to come by from any other earthly source. Nature affords us a kind of proof -- or at least a kind of reassurance -- that faith is not simply a form of wishful thinking, not something that we fashion in our minds to meet emotional needs of our own. Religion, experienced even at only the natural level, is an encounter with something beyond our ability to use, beyond our ability to fashion into something comforting, something that will reassure us that the world makes sense (on our own terms). Religion -- any religion worth man's attention--must be something overwhelming, something frightening, something beyond our ability to turn to our own purposes. That is what nature in its "sublimity" (to use the old-fashioned but expressive term) can still communicate to us. That, I think, is what D. H. Lawrence felt in New Mexico. It sure is what I feel when I go there.

I believe that I understand, more or less, what D. H. Lawrence felt and wrote about in his description of New Mexico. The immensity of nature that one confronts in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains is, of course, not the only source of religious experience that a person can have. (And I certainly am not willing to let D. H. Lawrence define that religious experience for me. I am in touch with a defining religious authority that Lawrence would not, did not, acknowledge--the Roman Catholic Church. It's the authority that enables me to distinguish between what is metaphysically true--and what is not--in the religious impulse of the Aztec, and the Brahmin, and the Buddhist, and D. H. Lawrence.) But nature, as Lawrence clearly perceived, is a source of one particular religious truth that is hard to come by from any other earthly source. Nature affords us a kind of proof -- or at least a kind of reassurance -- that faith is not simply a form of wishful thinking, not something that we fashion in our minds to meet emotional needs of our own. Religion, experienced even at only the natural level, is an encounter with something beyond our ability to use, beyond our ability to fashion into something comforting, something that will reassure us that the world makes sense (on our own terms). Religion -- any religion worth man's attention--must be something overwhelming, something frightening, something beyond our ability to turn to our own purposes. That is what nature in its "sublimity" (to use the old-fashioned but expressive term) can still communicate to us. That, I think, is what D. H. Lawrence felt in New Mexico. It sure is what I feel when I go there.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Why I Haven't Been Blogging

I was hiking in northern New Mexico.

To tell you the truth, I wish I still was.

"I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had."

To tell you the truth, I wish I still was.

"I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had."

-- D. H. Lawrence

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

The Sound of Chesterton, Belloc, and Lewis

My blogger buddy Keith Rickert commented that Basil Rathbone sounds the way he wishes G. K. Chesterton or Hilaire Belloc or C. S. Lewis sounded. I had heard recordings of Chesterton before. Here he is, in rather dim sound, delivering a BBC lecture on architecture. And I had heard some of Lewis's war-time broadcasts that eventually became Mere Christianity. Here's one. (Scroll down almost all the way, to the "Beyond Personality" clip.)

But I had never heard the sound of Belloc's voice and wasn't really sure what I imagined it might sound like. Keith was kind enough to steer me towards some examples. Here is the great (and odd) man sounding great (and odd):

You can follow the text of the first song, if you like.

What we have here, I believe, are three good reasons why people think speaking with a British accent makes you sound more intelligent.

But I had never heard the sound of Belloc's voice and wasn't really sure what I imagined it might sound like. Keith was kind enough to steer me towards some examples. Here is the great (and odd) man sounding great (and odd):

You can follow the text of the first song, if you like.

What we have here, I believe, are three good reasons why people think speaking with a British accent makes you sound more intelligent.

Bobby Thompson R.I.P.

He died yesterday at the age of 86.

The 1951 Major League season ended with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants tied in the pennant race, each with a 96-58 record. It was decided that the league championship would be settled in a three-game series. The Giants won the first game, the Dodgers won the second. In the third and deciding game, the Dodgers led 4-2 in the bottom of the ninth when Bobby Thompson, the Giants' third baseman, came to bat with two men on base. He took the first pitch, a fastball, for a strike. Then: